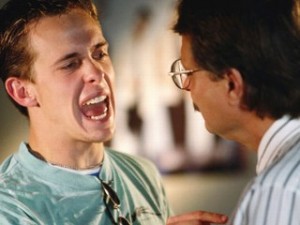

“Often, hurting teens lash out in anger at their parents when they’re actually angry at the illness.”

“Often, hurting teens lash out in anger at their parents when they’re actually angry at the illness.”Because you are the person responsible for your child, you are likely to be the target of their anger when life feels out of control for them. For once, you cannot fix their problems. Keep in mind that you are being graced with this unwelcome emotion precisely because you are the person who matters most to them. More, unlike their friends, you aren’t likely to leave if they explode at you.

You have my sympathy. You’re being called upon to carry out one of the most formidable tasks known to parents: convincing your teen that they are still lovable. In order to carry out this important job, you may first have to remind yourself that they are lovable. Remember that they don’t mean much of what they say to you. Even more, bear the following in mind:

More than anything in the world, they want you to approve of them.

I know it doesn’t feel that way. But deep down, they desperately want to see that you still hold them in esteem. Your view of them reflects back at them, although they don’t consciously realize it. So be lavish with your praise. I know it’s difficult to look for the good when your teen is making themselves so unappealing, but try. A simple, “One thing about you, dear, is that you never gossip” will go a long way. Try to come up with a sincere compliment each day. Even if they glare at you, persist. They are glaring at you because they don’t feel good about themselves.

You may feel partly responsible for your teen’s misery. Let’s say you initiated the divorce that is making them feel so miserable. An empathetic, “I’m sorry the divorce has caused you so much pain” can go a long way. You may not be able to change the way things are, but you can let them know that you regret how it has affected them. What do you have to lose? Your teen has already figured out that you’re not perfect. If you find that your empathetic remark results in a volcanic eruption of anger, sit quietly and listen. Let it flow. All that anger and resentment is much better outside than broiling inside. It may not be pretty to watch, but it won’t last. If you can’t think of anything to say without inciting more anger, simply say, “I hear you.” You can’t very well get in trouble for saying that now, can you?

Bear in mind that, especially in boys and men, anger can be a symptom of depression. The first time I heard that I was confused. It didn’t seem to make sense to me, but therapists and doctors now recognize that this occurs. If you have a boy, make sure the doctor is treating your son for the right thing.

A teen’s anger can be one of the most painful symptoms to bear. Just when you want to believe you’re doing well for your child, you are told that you a terrible parent. Be confident: this will end. Often, hurting teens lash out in anger at their parents when they’re actually angry at the illness. Give it time. If you feel discouraged, look at baby pictures or play videos of your teen’s childhood years. You might find them sitting down to watch with you while you relive better times together. At night, before you go to sleep, make a list of five things you do well as a parent. Beside the list, try to record five positive things about your teen. Do this every night, even if you repeat the same qualities. You will be surprised at how powerfully it can bolster and hearten you, giving you the courage you need to persist.

“As parents, we sometimes feel like we need to be in steady communication with our children, but teens need privacy.”

“As parents, we sometimes feel like we need to be in steady communication with our children, but teens need privacy.”